The evil that men do lives after them; The good is oft interred with their bones.

– Shakespeare, Julius Caesar

Most authors or would-be authors write out of some itch to outlast our heartbeat, to accomplish the improbable and have a mark we made live on beyond our life span, like our hominid ancestors scratching out forms on cave walls. We write to let an ephemeral spark inside of us feel less ephemeral, and we write to try to capture the unique life flickers of others who have mattered to us.

I’ve been thinking more about how we don’t just write to keep the dead alive, we read to keep the dead alive. It’s a good way to check if you’re giving yourself a shot at getting the most out of a book: Is that author, for you, alive, a human presence engaging your own, a peer in humanity, someone to converse with, argue with, be wowed by or not? Or are you reading the myth or received wisdom, reacting to the outsized persona of the emotional man-child Hemingway or convincing yourself before you crack Austen that you know just what you’re going to get, a musical chairs drawing-room dance of find-a-husband, or deciding that some science-fiction icon must not be worthy of you.

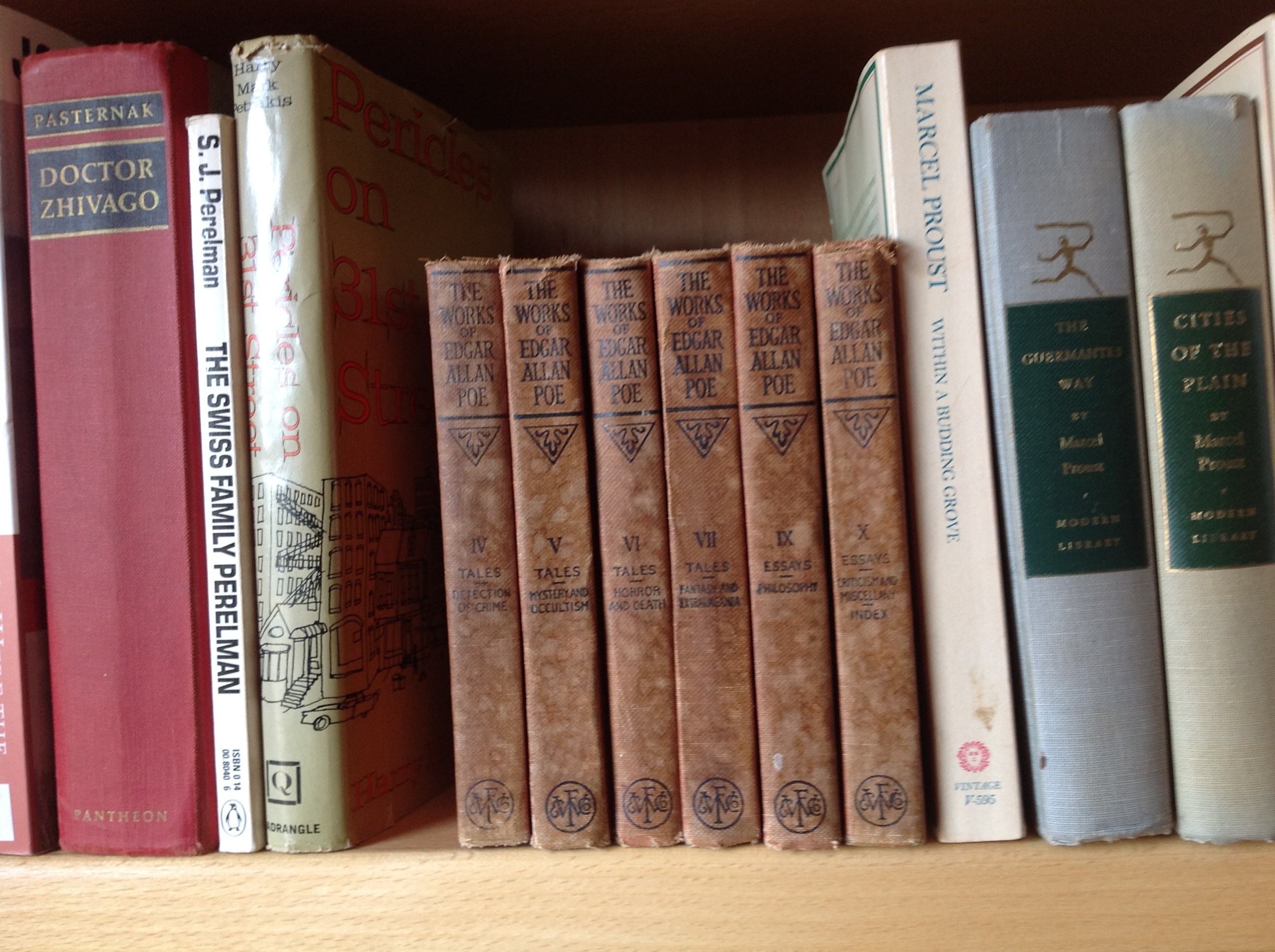

We can also read to keep the dead alive in another sense: reading pages that have been turned by another. I love reading a book with its own back story, and now at the Wellstone Center in the Redwoods we’ve added a remarkable collection of books, the Lotte and Alan Marcus Library, left to us by Lotte Marcus in memory of her late husband, the writer Alan Marcus, who made a name starting with his 1948 novel Straw to Make Brick, looking at postwar Germany, and wrote for MGM Studios, with half a dozen screenplays among his credits. His admirers included Saul Bellow (“I have as high an opinion of this talent as anything I have encountered in a long while,” Bellow once said of a Marcus novel), and he was a public intellectual in the old mold, widely read, deeply engaged in the life of the mind, who moved to the Carmel area in the 1950s with his remarkable wife Lotte, who grew up in Vienna and fled the Nazis with her family, resettling in Shanghai during her teen years, and now works as a psychologist.

It’s one thing to read Edgar Allan Poe online, and quite another to carry around a small faded-red hardcover, volume I in a 1904 collection of all of Poe’s writing. That’s what our current intern, Alex Paquin, is doing – and she told me it’s a thrill. The Poe books are part of our Marcus Library, where writers in residence and other guests here can enjoy them, and I myself had a gas reading Alan Marcus’ copy of the first James Bond novel by Ian Fleming.

In order to collect the books we’d gather for the Marcus Library, we headed down to the Marcus family home in the Carmel Highlands area and stayed in a beautiful room at one end of the long, narrow house, a cozy room with huge picture-glass windows, a fireplace and a large loft area up above. This very room, and its loft area, show up in David Hajdu’s book Positively 4th Street: The Lives and Times of Joan Baez, Bob Dylan, Mimi Baez Fariña, and Richard Fariña:

Once Joan brought Bob to meet a fellow writer, Alan Marcus, who lived with his wife, Lotte, and their three children a few hundred yards from Joan. A New Englander who had attended Brown, Marcus made his literary debut in 1948 with the acclaimed Straw to Make Brick, a novel inspired by the author’s military experience in the Second World War. Since moving to the Highlands in 1958, Marcus continued to write serious fiction and essays while quietly milking Hollywood for relatively easy money. He was a thoroughly rounded intellectual of a kind seemingly extinct, versed in science, philosophy, politics, and the arts; yet he had a feeling for popular culture. Marcus tended to intimidate Joan Baez, because she did not intimidate him. Joan and Bob had apparently decided to treat this visit to the Marcuses as a joke; Dylan was wearing blue jeans, a work shirt, a bow tie, and a top hat. He looked like a scarecrow of Eustace Tilly. Were he and Joan simply in a playful mood, or were they parodying Alan Marcus as an intellectual elitist? They never said a word about Dylan’s getup, and neither did the Marcuses. “I wasn’t sure what effect they had in mind,” said Marcus, “But it didn’t interest me. She seemed to want to show him off, and perhaps showing us off as the interesting family that lived up the road. So we sat back and waited for the conversation to flourish. It didn’t flourish. I think he was used to people being very obsequious with him, and I didn’t say, ‘Gee, can I touch you?’ or anything like that. He obviously felt that he wasn’t being celebrated enough, which he wasn’t. So he just sat there staring at us.” To break the mood, Joan walked up a flight of stairs to a loft area overlooking the others and started to sing. When she was finished, she walked down, Bob got up, and they left.

I met Alan Marcus only once, many years ago at the wedding of his daughter, my friend Naomi Marcus, to Colin Campbell, and only briefly then, but for me he lives on in stories like the one above from the book, and in the pages of these books he read and loved. Our books are mirrors onto our lives, and of course our loves. Thank you, Lotte Marcus, for your generosity in sharing this rich collection, still growing, which we hope will inspire writers of all ages here at WCR for years to come. Next up for me: a 1948 hardcover edition of Cry the Beloved Country by Alan Paton. Right at the top of the first page, up high in blue ink, Alan Marcus wrote his name and underlined it with a flourish, and he’ll be keeping me company on every page, urging me to stay alert, honest, open.

– Steve Kettmann

Want to receive Steve’s blog on writers and writing every week by email? Sign up below.